How games can teach us about choice

Would you kill one person to save five others? If you could upload all of your memories into a machine, would that machine be you? Is it possible we’re all already artificial intelligences, living inside a simulation? These sound like questions from a philosophy class, but in fact they’re from modern, popular video games. Philosophical discussion often uses thought experiments to consider ideas that we can’t test in real life, and media like books, films and games can make these thought experiments far more accessible to a non-academic audience. Thanks to their interactive nature, video games can be especially effective ways to explore these ideas. In this article we explore what games can teach us about choice.

You’re watching the movie The Road. Or you’re reading the original book by Cormac McCarthy. Despite drawing on the same material, these two experiences seem fairly distinct – one has top-notch actors and special effects, the other has your imagination filling in the roles, to the best of its abilities. (Your imagination, undoubtedly, is better.) One is a performance; the other is purely text based. One took thousands of people to create; the other took one man.

Then you’re playing The Last of Us (Naughty Dog, 2013). At its heart, it’s a very similar story and setting to The Road – it’s also a post-apocalyptic parent-child relationship with dark twists. Indeed, one might argue that it bears a closer relation to that film than the original book does, given that they both have cinematic treatments, actors and special effects.

But there’s one big difference between the game and the film. You’re involved. In The Road, you read or you watch. In The Last of Us, the player gets to do things, shoot enemies, solve physics-based puzzles, have scripted conversations with non-player-characters. You have choice in the world. It is, in essence, a first-person power fantasy.

Of all media, video games are the best at giving players agency; the freedom of modern games is what we celebrate about them the most. Games that use procedural generation, like Dwarf Fortress (Tarn Adams, 2006) or Spelunky (Mossmouth, 2008), have worlds that throw up endless variation that you can then explore with a limited set of tools. On the other hand, blockbuster games like The Elder Scrolls (Bethesda, 1994–2011) or Assassin’s Creed series (Ubisoft, 2007–) often give the player a huge amount of agency in handcrafted simulated environments.

Deus Ex and choice

Think of the Deus Ex games, such as Deus Ex: Mankind Divided (Eidos Montréal, 2016). In these near-future games, cybernetic augmentation has become commonplace, giving some augmented humans near-magical powers – imagine a world of cut-price Robocops and you won’t be far off.

The landscape of Deus Ex is full of decisions. They range from how to spend your in-game money, to societal moral decisions about not using your super-powered equipment on civilians and police officers, to whether you’ll follow the game’s plot or just explore the world, to decisions about how to approach an objective: stealth, violence, dialogue or one of your many cybernetic gadgets and disposable gewgaws. At the highest concept of the game, you get to select the path your world takes, the plot your character experiences and how the game ends.

In the competing visual media, only a handful of playful films like Clue and child-oriented adventure books like The Warlock of Firetop Mountain have ever given us a similar choice over which ending we consider final. And with these media, the viewer is still obliged to experience every ending to make that choice.

Mary DeMarle, lead writer on Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, has been designing and writing stories for games since 1998, and has worked on Myst III and IV, Homeworld 2, Splinter Cell and now the Deus Ex prequels.

‘I still remember the first day I started working in games. I’d come up with what I thought was a great storyline that hinged around a very specific player action and discovery. But when I presented it to my narrative director, he stopped me with a simple question: “Great! But what if the player doesn’t do that?” What if he or she doesn’t want to do that? Games are not passive experiences. As designers, we’re never sure what players are thinking at any given moment. They are the ones driving the action – and how they choose to do so can be very unpredictable at times.’

So it appears games, if they have one key differentiating feature from other media, are about agency – that is, choice. But what does it mean to have agency? To choose?

Well, as an example, the genre called ‘adventure games’ is all about choice, in the context of storytelling. Here you’re presented with a set of dialogue options and you select which one you think is correct. There’s often nothing else to do other than walk around and choose from interactions. Other than that, adventures are typically linear games where there’s only one storyline to follow through and your choices only matter if they’re correct – when you choose the wrong option or combine the wrong items you’re normally free to try again, with no consequences.

Think of LucasArts’ ancient piratical adventure Monkey Island (1990). This game is a spiritual antecedent of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, following the hapless Guybrush Threepwood as he seeks to rescue his love interest from the Ghost Pirate LeChuck. All the puzzles are completely linear, about selecting lines of dialogue or using objects on one another. For example, the only way to open the prison door is to carry a mugful of the bubbling, acrid drink grog from the Scumm Bar to pour onto the lock. To not do that is to stop playing the game.

False choice in Mankind Divided

In the narrow field of linear games, your only real choice is to decide whether to carry on with the game or not. That’s it. But even in sandbox and open-world games like Deus Ex, where the universe isn’t prescriptive and there’s ostensible freedom of movement and choice, you’re constrained. After all, the world of Deus Ex has been built by people and machines built by people. Says DeMarle:

‘The concept of choice is part of the franchise DNA. It underlies every design decision we make. Levels are constructed to offer multiple approaches and gameplay solutions, be they via combat, stealth, hacking, or social conversations; augmentations are designed and balanced to enable players to choose which ones suit their playstyles best. Narratives in the game not only have to offer deep choices and consequences, they need to reflect player decisions back to them later in the game. Honestly, I can’t picture a purely linear Deus Ex game – because it wouldn’t be Deus Ex if it were linear.’

Yet, because it’s all designed, every aspect of the world constrains your choice, one way or another. In particular, the general kinds of actions you can do in this world – walking, hacking, talking – are entirely the creation of other individuals. And when the player carries out an action in this game, the choices you’re making are intuitively not completely free – though they seem open, they’re in fact restricted. Every decision you make in this world is a Truman Show choice, where someone has designed every aspect of each option, and has a prepared response to every one. The options of what you can say to someone, how fast you walk or run, the shape of the city, the very perspective you see, the user interface; all of these took a team of hundreds who agonised over every element.

‘So what?’ you might say: ‘so my choice is constrained by these designers and the code machines of their creation. I still get to choose, though, don’t I? I have options and I select between them. Even that paltry choice earlier in Monkey Island – to play or not – is still a choice?’

Well . . . kind of. How do you make that choice? What are the criteria by which you choose? You, the individual, look at your preferences and look at the situation and select the option that you think will best fulfil your preferences. You do this by reference to the relevant facts you perceive in the world. When you choose whether an NPC lives or dies in Skyrim, you’re choosing based on who they are, who you want to be in that world and who you are in the real world. Yet nobody else steps in the way of your choices or forces you down a particular path. Of the options available to you, it seems that you could do any of them.

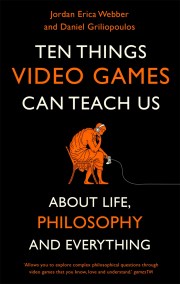

WOULD YOU KILL ONE PERSON TO SAVE FIVE OTHERS?

If you could upload all of your memories into a machine, would that machine be you? Is it possible we're all already artificial intelligences, living inside a simulation?

These sound like questions from a philosophy class, but in fact they're from modern, popular video games. Philosophical discussion often uses thought experiments to consider ideas that we can't test in real life, and media like books, films, and games can make these thought experiments far more accessible to a non-academic audience. Thanks to their interactive nature, video games can be especially effective ways to explore these ideas.

Each chapter of this book introduces a philosophical topic through discussion of relevant video games, with interviews with game creators and expert philosophers. In ten chapters, this book demonstrates how video games can help us to consider the following questions:

1. Why do video games make for good thought experiments? (From the ethical dilemmas of the Mass Effect series to 'philosophy games'.)

2. What can we actually know? (From why Phoenix Wright is right for the wrong reasons to whether No Man's Sky is a lie.)

3. Is virtual reality a kind of reality? (On whether VR headsets like the Oculus Rift, PlayStation VR, and HTC Vive deal in mass-market hallucination.)

4. What constitutes a mind? (From the souls of Beyond: Two Souls to the synths of Fallout 4.)

5. What can you lose before you're no longer yourself? (Identity crises in the likes of The Swapper and BioShock Infinite.)

6. Does it mean anything to say we have choice? (Determinism and free will in Bioshock, Portal 2 and Deus Ex.)

7. What does it mean to be a good or dutiful person? (Virtue ethics in the Ultima series and duty ethics in Planescape: Torment.)

8. Is there anything better in life than to be happy? (Utilitarianism in Bioshock 2 and Harvest Moon.)

10. How should we be governed, for whom and by who? (Government and rights in Eve Online, Crusader Kings, Democracy 3 and Fable 3.)

11. Is it ever right to take another life? And how do we cope with our own death? (The Harm Thesis and the good death in To The Moon and Lost Odyssey.)