How to Prepare Your Child for Loss

Telling children, especially young children, that their parent is about to leave them puts you in a quandary, as you would like their childhood to be as normal as possible, but on the other hand what is happening to them is not normal, and they do need to be prepared for it. In this article, we will learn how you can try to prepare your child for the loss of a loved one.

Children in their teens have probably had some previous experience of loss, either in their own lives or in those of friends, but this is less likely for small children. They, nevertheless, may have been acquainted with loss through the death of a pet, or having a grandparent die. In this case you have something to build on. However, although such previous experiences are helpful, they do not compare to the loss of a parent.

The website www.kidshealth.org has a very helpful list under the heading ‘Helping Your Child Deal with Death’. The list is for after a death has occurred, but it is just as useful for a pre-bereavement situation. Here it is:

- When talking about death, use simple clear words.

- Listen and comfort.

- Put emotions into words.

- Tell your child what to expect.

- Talk about funerals and rituals.

- Give your child a role.

- Help your child remember the person.

- Respond to emotions with comfort and reassurance.

If your partner has been ill for some time before the terminal diagnosis or before their situation deteriorates significantly, your children will already know something of what is happening and may already be fearful of the consequences. Sometimes, knowing exactly what is going to happen can relieve this anxiety, but they will still wonder what is going to happen to them. Will you still be in the same house? Will you have to move? Will they remain at the same school? And will they lose their friends? Some of this will be unspoken, perhaps because they do not want to upset you or cannot voice their fears. You may not be able to answer these questions with definite answers at this stage, but you can reassure them that you will do your best to keep things as normal as possible.

As a child I was farmed out to friends of my parents when my mother’s illness became particularly acute, and kind though these friends were, I absolutely loathed the experience. Anything would have been better than leaving home. Sometimes this is absolutely necessary, but do try to choose people who your child or children are comfortable with and who have roughly the same attitude to child-rearing as you have in terms of boundaries and rules. It was the changes to these latter that I found baffling. Things that my mother allowed me to do were now forbidden and this seemed to add insult to injury.

Try to make sure that any time you spend with your children is of the highest quality in terms of your involvement and attention. Ask friends to replace your partner and yourself in the activities that they might normally have had with you, but warn them in advance that the child might resent this and find it an intrusion. Rope in family and friends to keep things as normal and regular as possible in terms of their activities. Ask other parents to take on some of the burden of transporting your children to shared regular activities. Your friends will be glad of something specific they can do to help you.

If you and your partner spend time in planning their funeral, make sure that you involve your children in this activity, even though it might be difficult for them. Would they like to read a poem or play an instrument? Let your children decide if they want to take part, and how. Make it as fun as possible. How would they like to remember their parent, step-parent or adoptive parent? Would they like to help you make a video, put photographs together or act out an incident that meant a lot to them? Much of this depends on how able the dying parent is to be involved, but the effort will be well worth it afterwards, as your child is likely to adapt more quickly to the loss than if it had not been discussed or acted upon. If you think your children might need professional help, try Jigsaw or Winston’s Wish.

You will also have to decide how much you want your children to see of their dying parent. Physical changes can be very difficult for young children and also the not so young, who may have had no experience of the physical changes that illness can bring. I can still remember waking up in a hotel bedroom aged about five to find my father had got sunstroke – his face was very swollen and his eyes invisible – and being absolutely traumatised. Such illnesses as cancer or motor neurone disease, which leave their inimitable marks on the face and body, or seeing a parent wired up to a life-support system, can be very distressing and stressful to witness for children, who do not really understand what is going on. This is a very difficult decision to have to make on your part, but you know your children best and as long as you have thought through the implications, you will make the right choices.

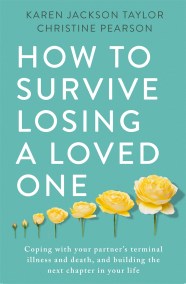

A practical, empowering guide to navigating your partner's diagnosis of a terminal or life-limiting illness, or death.

Receiving the news that your partner has a terminal or life-limiting illness, or has died unexpectedly, is among the worst experiences in life. At a time when you are least able to cope, you are faced with a multitude of difficult decisions, some of which must be made quickly. What you need is a friend who has experienced everything you are about to face, who can support you as you navigate some tough, important choices.

This book is that friend. There is plenty of information out there but where to start looking? What information is needed and how can it be accessed? What decisions are essential in the immediate term and what can be left until later? Throughout the book, the emphasis is on protecting and supporting those left behind by presenting almost every choice you may need to make and the possible implications of each decision.

You will learn:

- The importance of creating a will, arranging power of attorney, organising advanced decisions of treatment, and even getting married or entering a civil partnership

- What you are entitled to from the state, the NHS and your employer

- How to stabilise your finances and prepare to run a household alone

- Where your partner ought to be during treatment and/or palliative care, and how to go about achieving this

- Which decisions need to be made after death, from planning the funeral to accessing your partner's estate

- How to navigate the grieving process and take control of a happy future

No matter where you are in the process, How to Survive Losing a Loved One is a comprehensive, practical and empowering guide to coping with your partner's terminal illness and death, and building the next chapter in your life.